Polygenic risk scores calculate how our genetic makeup shapes our likelihood of developing conditions ranging from heart disease to cancer. Research powered by UK Biobank’s vast amount of genetic data is revealing their promise for personalised healthcare – and their limitations. What role will polygenic risk scores play in the future?

What are polygenic risk scores?

A polygenic risk score, or PRS, is a way to calculate how our genetic makeup affects our risk for developing a disease.

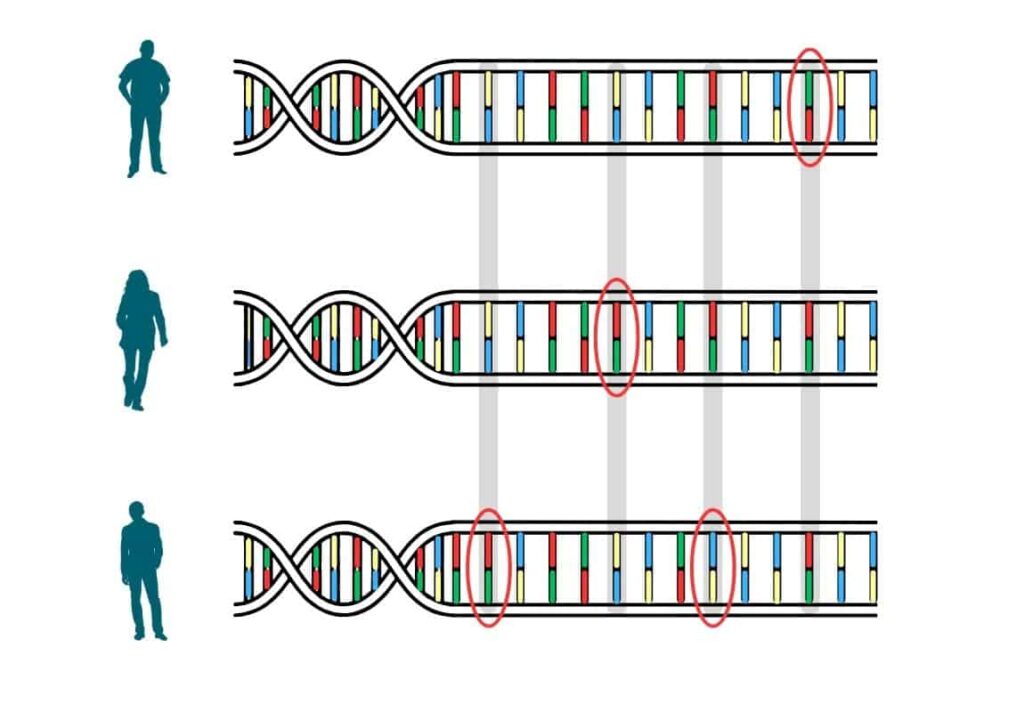

All humans’ DNA is near-identical. It’s the slight differences that make us unique. Many of these genetic differences – called variants – are inherited. Some affect things such as height or hair colour. Others can make us more prone to certain health problems. Researchers have discovered many statistical links between variants and diseases by comparing the DNA of people with and without those diseases.

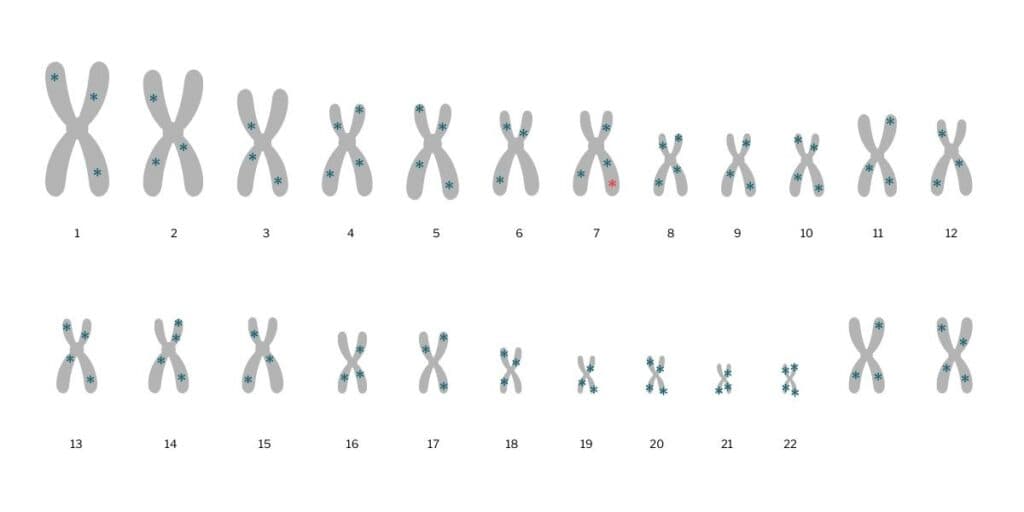

Some diseases are caused, in large part, by variants at a single point in our DNA – meaning within a single gene. An example of one of these ‘monogenic’ diseases is cystic fibrosis.

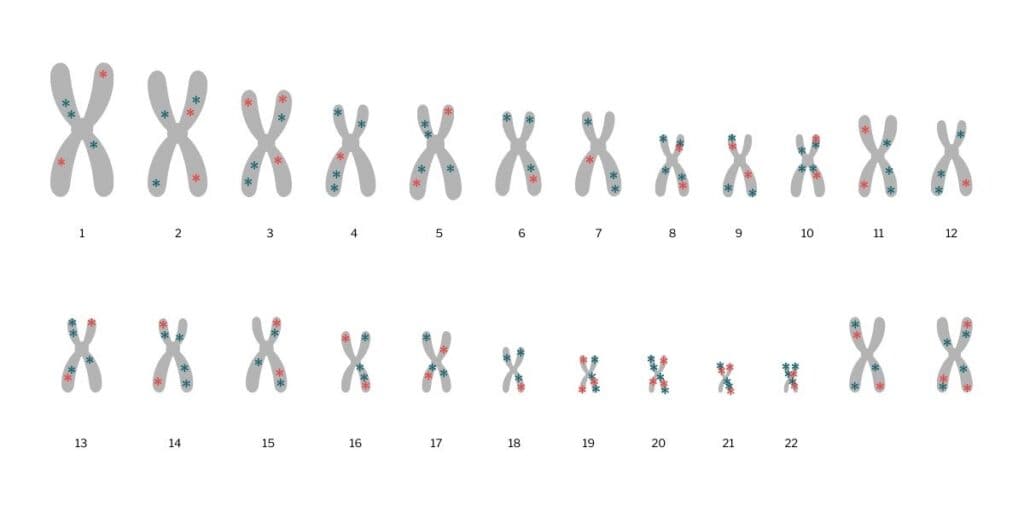

Most diseases are polygenic: they are affected by variants in many genes. A PRS adds up the impact of each of these variants to calculate the risk for a particular disease in comparison with a person that has a different genetic makeup. Each variant contributes differently to risk – some have a big impact, others only a small one. A higher PRS indicates a higher risk.

For many common yet complex conditions, such as type 2 diabetes or heart disease, genetics are not the only contributor to disease risk. Environment, personal circumstances and lifestyle also play a part – in many cases, a larger one than our genetic makeup.

Why do we want to calculate polygenic risk scores?

A PRS can add another layer of information to factors such as family history, ethnicity, environment and lifestyle that doctors consider when trying to find out who among their patients has the highest risk of becoming ill. This is particularly important for people who are in the early stages of a disease and may not have symptoms yet, which makes it difficult for doctors to diagnose their condition.

There’s a real need to identify [higher risk] cases so we can target screening and treatments more effectively, and [polygenic risk scores] give us a potential way forward.

Dr Amit Khera, Harvard Medical School, US

“Individuals who are at several times the normal risk for having a heart attack just because of the [cumulative] effects of many [genetic] variations are mostly flying under the radar”, cardiologist Amit Khera from Harvard Medical School, US, explained to The Harvard Gazette.

“If they came into my clinical practice, I wouldn’t be able to pick them out as high risk with our standard metrics. There’s a real need to identify these cases so we can target screening and treatments more effectively, and [PRSs] give us a potential way forward.”

How are UK Biobank data involved?

In 2018, researchers used genetic data from UK Biobank participants to develop PRSs for five common diseases: coronary artery disease, breast cancer, type 2 diabetes, atrial fibrillation and inflammatory bowel disease. Although the concept of PRSs was not new at the time, this work was a breakthrough for the field: it was the first time PRSs were created using data from such a large number of people.

There can be hundreds or thousands of points in our genetic code where a variant contributes to a higher (or lower) likelihood of developing a disease. This means genetic data from a huge number of people is needed to reliably detect variants and figure out how they are linked to health and disease.

All half a million UK Biobank participants donated a sample of their DNA – in the form of a small amount of blood – during their first, ‘baseline’ visit to a UK Biobank centre. Access to this enormous amount of genetic information has allowed researchers to create more precise PRSs for a larger range of diseases. New PRSs are being developed with UK Biobank data all the time.

What diseases can polygenic risk scores predict?

In 2024, 12 GP practices in the North of England tested whether PRS could improve prediction of people’s risk of heart disease. Anyone who has been to an NHS health check might have come across QRISK: it’s a score that estimates our risk for developing heart disease or stroke within the next ten years. It takes into account things like age, sex, and personal and family medical history as well as measures such as blood pressure and liver function.

Adding a PRS to QRISK could help GPs to decide who needs preventative treatments such as statins, explains Yusuf Soni from Riverside Medical Practice in Stockton-on-Tees, UK, who was one of the GPs taking part in the trial. Overall, GPs in the trial reported that knowing their patient’s PRS would change their treatment plan in 13% of cases. Soni also noticed that his patients found discussions about their genetic risk helpful: “Patients that might not have taken up [medication or lifestyle changes] actually did.”

A large proportion of prostate cancer cases detected using a [polygenic risk score] would not have been detected using the current diagnostic pathway.

Professor Michael Inouye, University of Cambridge, UK

Another trial looked at whether a PRS can pick out men who are high risk for prostate cancer – or already have it. Current tests aren’t very specific: they can miss some cases while flagging others as more severe than they really are. “A large proportion of prostate cancer cases detected using a [PRS] would not have been detected using the current diagnostic pathway,” PRS researcher Michael Inouye from the University of Cambridge, UK, told the Science Media Centre.

For some conditions, such as psychiatric disorders, PRSs aren’t working well. This could be because researchers haven’t yet found all the possible variants that affect disease risk or because a disease is heavily influenced by factors that have nothing to do with our genetic blueprint. False positives – results that say an individual is at high risk when they aren’t – can lead to overdiagnosis and unnecessary stress.

Some in vitro fertilisation companies in the US are using PRSs to screen embryos. The practice isn’t legal in the UK, is beset by ethical concerns and lacks scientific evidence.

When will we see polygenic risk scores in GP practices and clinics?

“Realistically, it will likely be years for the NHS to use PRSs routinely,” Inouye said. “It will require investment in infrastructure, generation of genomic data, training for healthcare [practitioners] and potentially access to counselling for patients.”

There are plans for the NHS to start using PRSs by the end of the decade. One of the UK’s private healthcare providers, Bupa, has already started to offer its clients PRS tests for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, breast cancer and prostate cancer.

“Just having genetic tests that could deliver results as part of polygenic risk analysis is not enough: a whole service is needed to support those who end up in that type of ‘production line’,” says Alan, UK Biobank participant and retired oncologist. “There must be support for people to understand what the risk scores mean.” He also points out that there’s little value in knowing your risk if there’s no way to prevent or treat the condition.

Some conditions, such as mental health disorders, are unnecessarily stigmatised, says PRS researcher Josephine Mollon from Harvard Medical School, US: “You just don’t want to expose individuals unnecessarily to that stigma and that stress of saying you’re likely to develop this [condition] if that’s not the case.”

It could potentially lead to lifestyle changes and better assessments and diagnosis of disease, but this is very sensitive data with significant implications for the individual, so this would need to be carefully managed.

Alison, UK Biobank participant

UK Biobank participant Alison can see the benefit of knowing her genetic risk, but shared concerns about how the data could be used by agencies such as health insurers: “It could potentially lead to lifestyle changes and better assessments and diagnosis of disease, but this is very sensitive data with significant implications for the individual, so this would need to be carefully managed.”

Many researchers believe that, eventually, PRSs will form a crucial part of clinical practice. And while trials such as the prostate cancer PRS was “a big step along the path to clinical implementation, it is still a long road”, Inouye said.

References

- Nature Genetics, August 2018

- European Journal of Preventative Cardiology, January 2024

- New England Journal of Medicine, April 2025

- Biological Psychiatry, September 2025