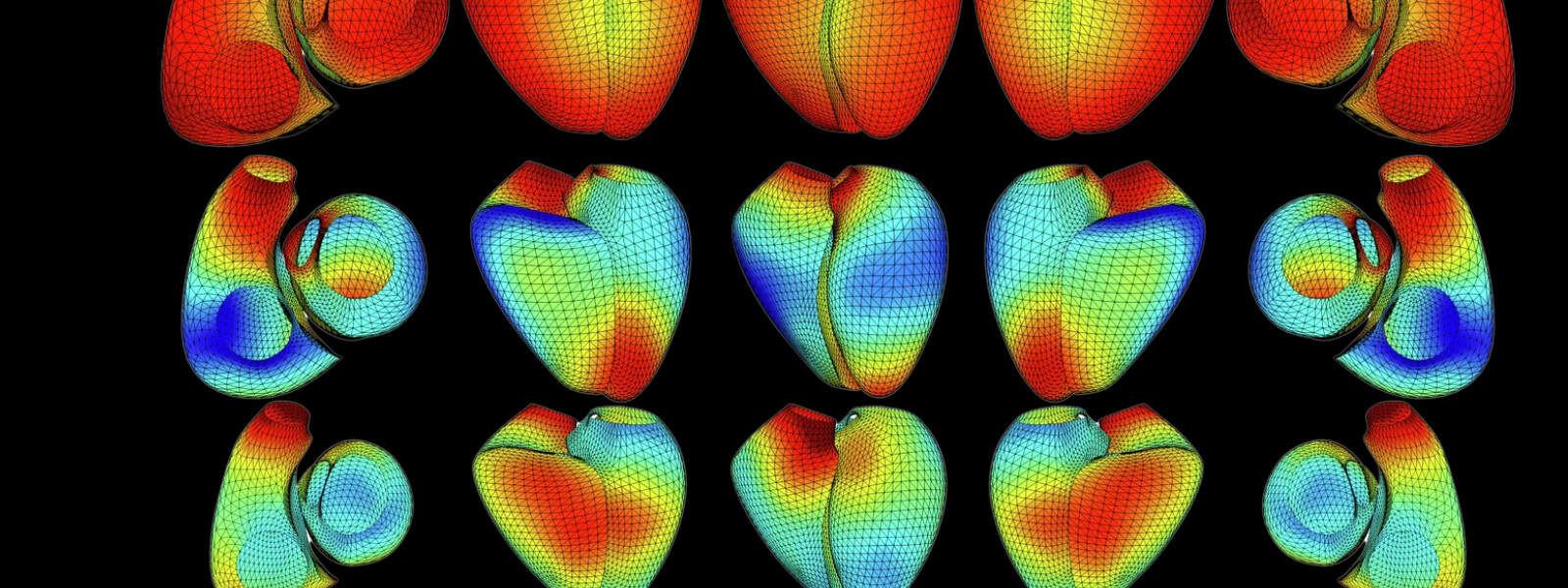

A unique 3D atlas constructed from UK Biobank participants’ heart scans reveals how certain shape variations increase heart disease risk.

Summary

A first-of-its-kind 3D heart atlas, created from more than 45,000 UK Biobank participants’ heart scans, shows how subtle differences in the organ’s shape are linked to conditions such as stroke or diabetes. The atlas could form the basis of technology that might eventually make it easier and faster for cardiologist to diagnose life-threatening heart disease.

Researchers have constructed a first-of-its-kind atlas of heart shapes from more than 45,000 UK Biobank participants’ heart scans. Some subtle shape differences are linked to disease, so analysing the organ in minute detail could help clinicians to identify people who are at risk of stroke, atrial fibrillation and other heart conditions.

Certain aspects of the heart’s structure – such as heart chamber volume – are already measured to assess the organ’s function. “These measures are actually very simplistic,” says Wenjia Bai, who works independent of the study team on heart-image analysis at Imperial College London, UK. Heart size alone tells us little about the organ’s function, just as body weight tells us little about someone’s body shape – for example if someone is tall and lanky or short and stout.

No one had made a three-dimensional representation like this.

Julia Ramírez, University of Zaragoza, Spain

Machine-learning analysis of magnetic resonance images from UK Biobank participants has now revealed 11 ‘shape components’ that capture most of the variations in heart geometry in a first-of-its-kind 3D model. Each shape component describes some of the heart’s features including the organ’s size, roundness and tilt. “No one had made a three-dimensional representation like this,” study team member Julia Ramírez from the University of Zaragoza, Spain, told El País.

The team found that people with rounder hearts have a higher risk of atrial fibrillation, characterised by an irregular and often fast heartbeat. A smaller heart is associated with diabetes, while variations in the height-to-width ratio are linked to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a disease in which the heart muscle becomes thickened.

“Can we develop some tools for some of these measurements,” asks co-leader Patricia Munroe from Queen Mary University of London, UK. “Might they add a bit more value to what we currently use in the clinic?”

From genes to drugs

Heart shapes are, at least in part, heritable. The team also analysed UK Biobank participants’ DNA and uncovered 43 DNA sections that influence the heart’s shape – 14 of which had never been linked to any heart traits before. Identifying genes that are associated with disease-prone heart shapes could point towards new drugs to treat these diseases, Bai suggests.

Munroe says she now wants to move from the static shape atlas, which captures the heart at rest, to a dynamic representation that shows shape differences as the heart contracts and relaxes. Once it becomes clear how the heart’s shape influences its pumping ability, scientists could create a digital simulation of someone’s beating heart from a simple scan, Bai explains.

If such technology makes it into the clinic, it could make it easier and faster for cardiologist to diagnose life-threatening heart disease. An artificial-intelligence algorithm that turns regular heart scans into 3D images already helps NHS doctors to quickly decide whether someone needs heart surgery.

Related publication

- Nature Communications, November 2024

Header image credit: R Burns et al, adapted from source, Nature Communications