Learn about the different ways your information and samples have been used to make groundbreaking scientific discoveries that improve public health.

On this page

- What research have I contributed to?

- How have my biological samples been used?

- How have my images been used?

- How have my questionnaire data been used?

- How have my health records been used?

- How have my activity monitor data been used?

- How have my physical measurements been used?

- How have my lifestyle, health and other data been used?

What research have I contributed to?

Your data has been used in more than 18,000 peer-reviewed scientific papers including many on the major causes of ill health, such as:

- Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other lung conditions

- Cancer

- Dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, stroke, migraine and other brain conditions

- Depression and other mental health conditions

- Diabetes

- Hypertension, heart attack and other cardiovascular conditions

- Infectious diseases, including COVID-19

- Osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and other musculoskeletal conditions

How have my biological samples been used?

The DNA and other molecular components in the blood and urine you donated hold invaluable information about your body’s genetic makeup, biochemical processes, organ function and more.

Genetic data

The genetic information UK Biobank collected comes from your blood samples. We worked with several biotechnology companies that analysed your DNA in various ways.

In 2023, UK Biobank became the largest whole-genome dataset in the world: we now have transcribed every one of the three billion building blocks that make up each participant’s genetic code.

Researchers use UK Biobank’s genetic data to, for example, develop ‘genetic risk scores’ that estimates how likely someone is to develop a particular health condition. An NHS pilot has shown this genetic risk score to be a useful addition to current tests that help to predict who has a high risk of developing heart disease. This could eventually allow doctors to offer their patients more tailored strategies to prevent these conditions.

Biomarker data

UK Biobank has worked with several biopharmaceutical companies to analyse certain molecular compounds in your blood and urine samples.

Our DNA can be thought of as a huge, mostly unchangeable recipe book, while other biomolecules – such as proteins and metabolites – reflect the dishes that are currently being prepared in our bodily kitchen. This gives researchers an up-to-date picture of what is happening in the body.

For example, researchers analysed 3,000 proteins in the blood of 54,000 participants. They found that four of these proteins can predict whether someone is likely to develop dementia up to 15 years before they are diagnosed. This is important because early diagnosis and treatment are key to living well with dementia (and other long-term health conditions).

Plans are underway to measure thousands more proteins in the blood of all 500,000 participants. Looking at proteins on such a huge scale has the potential for breakthroughs in detecting and treating dementia, heart disease, depression and many other conditions.

Some 20,000 of you will also remember regularly collecting finger-prick blood samples of yourselves and some of your relatives at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. This allowed researchers to show, for example, that 88% of people retained antibodies against the virus for at least six months after a COVID-19 infection.

How have my images been used?

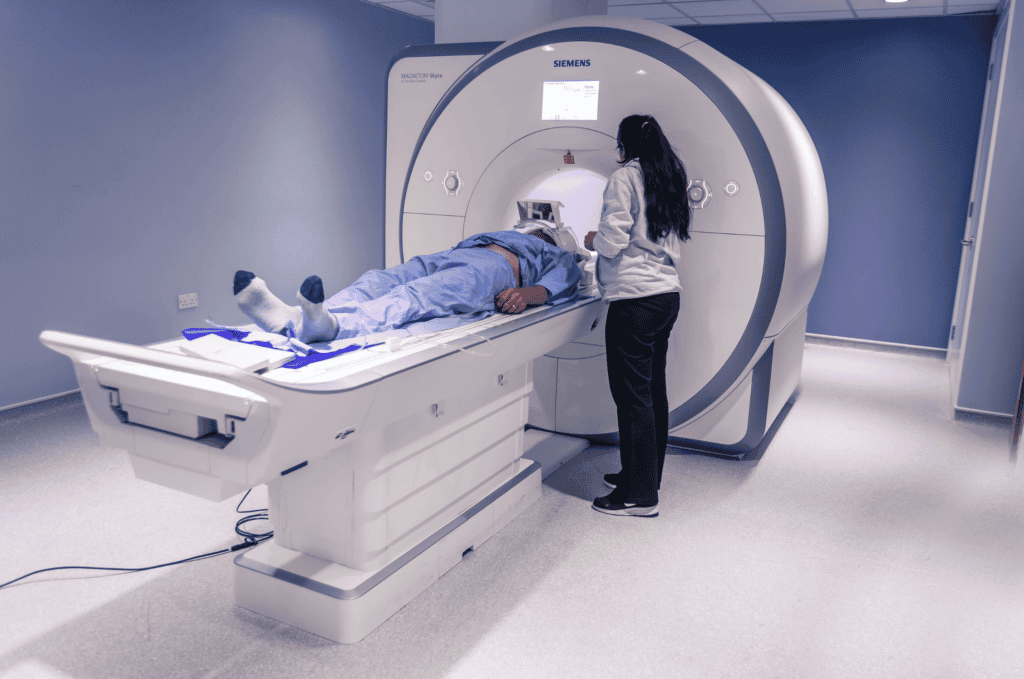

UK Biobank is the world’s largest health imaging study: almost 100,000 of you have been to one of our imaging assessment centres. Your magnetic resonance, ultrasound and bone-density images allow researchers to investigate on an unprecedented scale how genetics and lifestyle influence the structure and function of internal organs.

For example, researchers have used your bone-density (DEXA) scans to create an artificial-intelligence tool that can spot subtle hints of osteoarthritis in hips and knees. Similar automated systems could eventually help to catch early-stage arthritis even when doctors aren’t specifically looking for it.

Some of you have already attended a second imaging visit. Looking at changes over time is essential for researchers to understand how conditions progress and what can be done for people to stay healthy for longer.

Some of you attended an additional imaging visit during the COVID-19 pandemic. This made UK Biobank the only research study in the world that has scans taken before and after people contracted COVID-19. For example, brain scans collected during these visits revealed that even mild COVID-19 infections seemed to damage the brain’s ‘smell centre’.

How have my questionnaire data been used?

Open questionnaires

Some of our questionnaires are still open. Take a look at which you can complete if you haven’t already, to help us build on our existing data with new insights into your health.

Many of you have regularly completed our online questionnaires on topics such as chronic pain and sleep. Your answers give researchers insight into your lifestyle and experiences – things that aren’t captured well in medical records.

For example, as part of an effort to uncover how genetics influence effective treatment of depression, researchers found that clinical studies can miss the nuanced effects of antidepressants. In UK Biobank’s mental health questionnaire, two thirds of participants with depression saw their symptoms ease when they found the right medication. In clinical studies this percentage is often much lower because they only note if a medication eliminates symptoms entirely.

How have my health records been used?

When you first joined UK Biobank, you agreed to allow us to collect your electronic medical records, including coded GP records, data on hospital stays, cancer diagnoses and causes of death. This information lets researchers know what health conditions you are experiencing over time.

For example, researchers used your hospital and GP records to show that people who had less sugar in early life have a lower risk of some chronic health conditions much later. Discoveries like this could help to create better dietary guidelines for children and might make food companies consider reducing the sugar content in baby products.

Primary care data is particularly valuable to give researchers insight into conditions that are largely diagnosed and managed by GPs, such as diabetes, dementia and mental ill health. We have long been able to access this data for the 11% of you living in Scotland and Wales – but not most of our England-based participants. This might soon change.

In October 2024, a government directive placed the responsibility for these data into the hands of NHS England. This has taken the burden off busy and overworked GPs, and will allow us to apply to access all our participants’ primary care data.

During the pandemic, emergency legislation allowed us to access all our participants’ GP data for COVID-19 research. Hundreds of scientific studies resulted from this data, including some that unravel why some people become very ill when they catch COVID-19.

How have my activity monitor data been used?

The information from 100,000 of you who wore our activity monitor for a week on at least one occasion have given scientists insight into how exercise and health are linked. Often, researchers have to rely on people’s (potentially fuzzy) memory of their activities for investigating these correlations.

For example, researchers used these data to show that cramming one’s weekly activity into two days seems to be as healthy as working out daily. This is somewhat different to the NHS recommendation of spreading out one’s exercise evenly over four to five days each week.

How have my physical measurements been used?

The various physical measurements – height, weight, lung capacity, grip strength, blood pressure and more – allow researchers to look at how health conditions impact bodily functions. For example, researchers found that grip strength might be a better predictor for someone’s risk of cardiovascular disease than their levels of physical activity.

Up to 200,000 of you did vision and hearing tests when you joined the study. These data have shown, for example, that hearing loss is linked to a greater risk of dementia. The study is one of many that try to untangle whether hearing aids could reduce someone’s dementia risk.

Images of participants’ retina – the cells at the back of the eye – have been used to create an artificial-intelligence algorithm that can predict someone’s risk of heart disease from these images. This could eventually help doctors to offer more personalised prevention strategies to people who might be more prone to heart health conditions.

How have my lifestyle, health and other data been used?

During your visits to one of our centres you provided us with a huge amount of other invaluable information. When speaking with a study nurse or when answering questions on a computer, you told us about yourself, where you live, your education, employment, family history, medical conditions and so much more.

Researchers have used this information to see how our social environment, medical history and lifestyle influence health over time, which will contribute to more effective public health policies, and personalised advice and treatments. For example, one study found that participants living in residential areas with more green spaces have a lower risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).